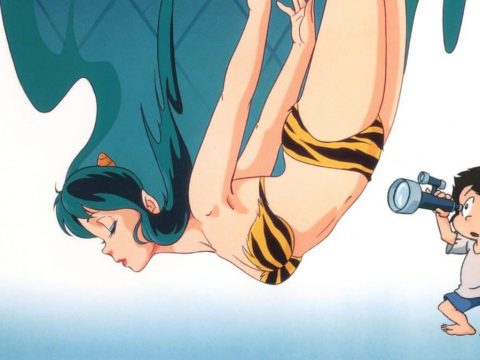

One of Japan’s most celebrated and beloved comic book and anime creations, Urusei Yatsura delivered a total of just under 200 high-voltage weekly blasts of supernatural-and-alien-augmented battle-of-the-sexes to TV audiences in the early-to-mid 1980s. At its core was the sitcom relationship between lecherous high school student Ataru Moroboshi and his jealously devoted green-haired, tigerskin bikini-wearing, accidental alien/demon fiancée Lum, but with its frequent intrusions of sci-fi and supernatural concepts, it was able to play out its essentially intimate rom-com drama on a galactic scale when it felt like, making it a rare example of a TV comedy that was primed to translate well to the big screen.

Urusei Yatsura ended up spinning off six movie versions, and we’re going to take a look at all of them here in an attempt to sort the best from worst.

6. URUSEI YATSURA 6: ALWAYS MY DARLING (1991)

It was a close-run thing for the worst film in the Urusei Yatsura series, but the final film, released in 1991 for the 10th anniversary of the TV show, just about claims this dubious honor.

It was a close-run thing for the worst film in the Urusei Yatsura series, but the final film, released in 1991 for the 10th anniversary of the TV show, just about claims this dubious honor.

One of the fundamental problems with Urusei Yatsura lies in the central drama between these two extreme parodies of male and female romantic archetypes: lazy, libidinal, Ataru, perennially unable to settle, and jealous, possessive Lum, singularly fixated on her man. The drama between these two figures depends on them never really evolving, which makes it difficult to draw the sort of arc of character development that a movie narrative usually requires. Always My Darling does this particularly badly, with Ataru reduced to a yapping, howling animal with no capacity for thought beyond the next thing in a skirt that crosses his path, while Lum goes through the motions of trying to improve him only to give up and settle for a return to the status quo.

Instead, the narrative arc focuses on two new characters, “princess of the universe” Lupica and tofu salesman Rio, whose mutual affection is smothered by their social hangups – as a woman, she needs him to make the first move, while he feels his social status prevents him from confessing his feelings to her. Urusei Yatsura is often at its best when dealing with Japan’s social and class hangups, and there’s something sweet in the stuttering romance between these two, even as the plot devolves into Lupica’s attempt to essentially roofie Rio using a love potion, which then spins predictably out of control.

The love potion mcguffin also reveals something quite sad at the heart of the Urusei Yatsura worldview. It asks the question, “If you could push a button and it would make a person love you unconditionally forever, would you do it?” When presented with this question, nearly everyone in the Urusei Yatsura universe answers yes without hesitation. It’s a universe where love is warfare, pursued through strategy and manipulation and delivering nothing but suffering and torment. Ataru’s habitual horny hound dog harassment of any woman he sees might be shallow and basically pretty despicable, but at least he’s happy. When the love potion accidentally fixates him on Lupica alone, his pursuit of her becomes colored with abject, howling despair. Lupica and Rio at least get to fly off into the sunrise together, but those characters left on Earth are doomed to the same cycle of endless disappointments.

All of which would be interesting if the film was better. However, with a central conceit that might have made a passable 22-minute episode of the TV show, the film’s hyperactive energy becomes repetitive and frustrating quite early on as it draws the idea out without ever really deepening it in any way.

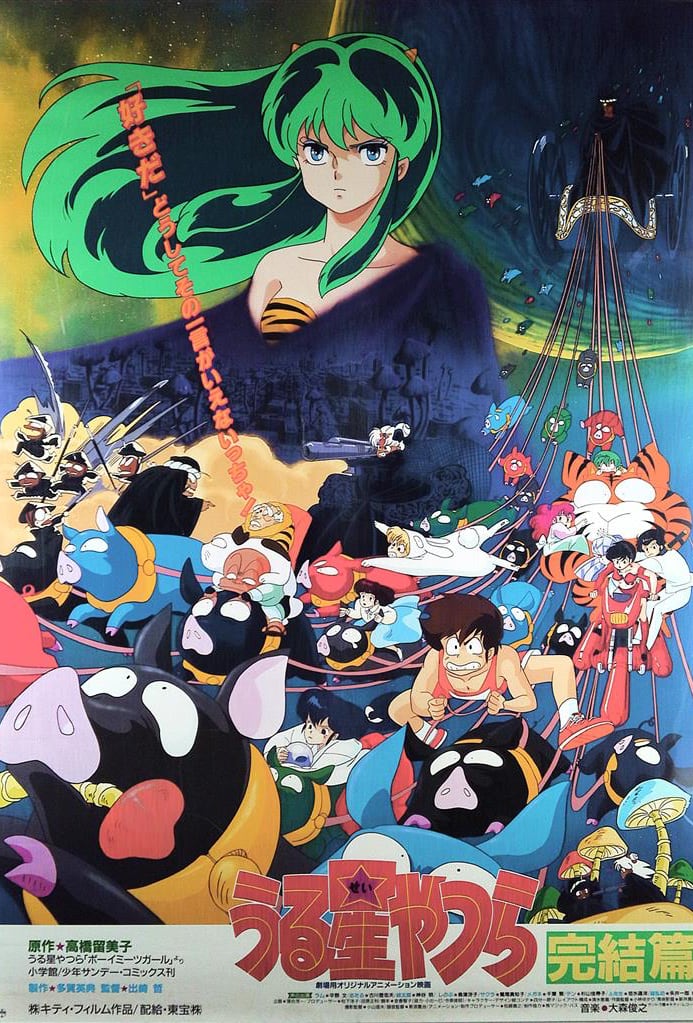

5. URUSEI YATSURA 5: THE FINAL CHAPTER (1988)

Almost as mediocre as Always My Darling, The Final Chapter promises closure that it never had any intention of delivering. Instead, what it offers is a reheated rerun of story beats we’ve seen before.

Almost as mediocre as Always My Darling, The Final Chapter promises closure that it never had any intention of delivering. Instead, what it offers is a reheated rerun of story beats we’ve seen before.

It’s a recurring theme in Urusei Yatsura stories: either Lum or Ataru is spirited away by a lovestruck alien or supernatural presence, the other must temporarily overcome their jealousy/lechery in order to rescue them, we are teased by the possibility that this time things might be different and their relationship will grow, and then a space ship crashes into the school, a giant tiger-cow starts running loose, a tsunami crashes through the school corridors, Ataru starts chasing girls again, Lum electrocutes him, everyone joins in the chaos and normality is restored. What separates a good iteration of the series from bad ones like this is the individual take of the creators behind it – a unique insight into the nature of the repeating core dynamic between Lum and Ataru, a philosophical take on the world of which they are part, a fresh narrative approach, a distinctive visual style.

This time round it’s Lum who is kidnapped by a lovelorn alien suitor, at least initially. Often in Urusei Yatsura, these new characters are an opportunity for the writers to work with a fresh canvas and inject some new life into a format that’s otherwise locked into a repetitive emotional dymanic. In The Final Chapter, the characters of Rupa and Carla are instead used to mirror the central dynamic of Ataru and Lum – both cases of indecisive men running from powerful women. There’s a theme in here somewhere of partners testing each other’s love, with the climax, such as it is, calling back the the game of tag that first threw Lum and Ataru together – she willing to let the fate of the Earth hang on Ataru’s willingness to confess his love, he believing the very existence of those stakes make any declaration of love meaningless. The drama they play out in these closing scenes is essentially the common one (at least in Japan) of, “I need to hear you say you love me,” versus, “If our love is real, you shouldn’t need to hear me say it.”

Despite clearly having an emotional take on the central character dynamic, however, what The Final Chapter lacks is any sense of style, pacing or consistency of character. At 85 minutes in length, it is one of the shortest films in the series, yet so disjointed is its pacing, so muddled is the character development, that it feels like one of the longest.

4. URUSEI YATSURA 3: REMEMBER MY LOVE (1985)

With this third movie in the series, we move away from the post-series one-offs and get into the films that were produced concurrently with the ongoing series and made by people who had been intimately involved in the series itself.

With this third movie in the series, we move away from the post-series one-offs and get into the films that were produced concurrently with the ongoing series and made by people who had been intimately involved in the series itself.

That extra familiarity with the world and the characters shows in the greater depth and more richly realized artistic vision that we find in these earlier Urusei Yatsura films. The opening scene of Remember My Love – a rickety, horror movie house in a rotten swamp with a creepy, mechanical doll mindlessly repeating the lines of an old witch’s curse – sets up a distinctive and creepy atmosphere right from the start (the same scenario is revisited later on but played for laughs in a neat narrative flourish). The eeriness cranks up a notch with the appearance of a creepy theme park, which haunts the gang with past or alternate versions of themselves, climaxing with Ataru being turned into a hippopotamus by a dashing, debonair stage magician.

Remember My Love walks a fine line between the eerie and the comedic, aided by characters who react straightfaced to the story’s sudden lurches into outright absurdity. This enables an emotionally wrought scene between two lovers to retain all its weight as drama despite the fact that one of them is a bright pink and very unhappy hippo, while at the same time the fact they play it completely straight enhances the humor of the absurd transformation.

In this movie, Lum is taken away by a young alien boy who has developed an oedipal obsession with Lum’s smile, and blames the unhappiness visited upon her by Ataru’s constant doomed attempts at infidelity for the loss of the purity and innocence that smile represents. For Lum, this change in her is simply a reflection of the growing complexity of her life, but for the boy Ruu, living in his pirate galleon marooned in a sea of frozen crystal, it represents loss.

The theme of loss is one that runs through many Urusei Yatsura films. The characters are forever 17 years old, on the cusp between childhood and adulthood. The colorful, carnivalesque parade of their youth is constantly unicycling away from them, and the gray reality of adult life awaits. Even mediocre entries in the series like The Final Chapter recognize this in some small way, but Remember My Love director Kazuo Yamazaki is perhaps the one who most extensively develops it. The characters of Tomobiki Town (seemingly located somewhere in the western Tokyo suburb of Nerima) lead uniquely colorful lives, arrested in a free-and-easy adolescent state of play and adventure, and Lum is both the instigating agent of that explosion of color and its totemic figure. Take away Lum and that color drains out of their lives. What Remember My Love asks is whether the loss of innocence also has to mean the loss of magic from our lives, and in that sense director Yamazaki is similar to the character of Ruu in treating Lum as something cosmic, symbolic and divine. Unlike Ruu, however, Yamazaki recognizes Lum’s own agency and right to make decisions about her own life, even when those decisions lead her to do self-evidently unwise things like fall in love with a schlub like Ataru.

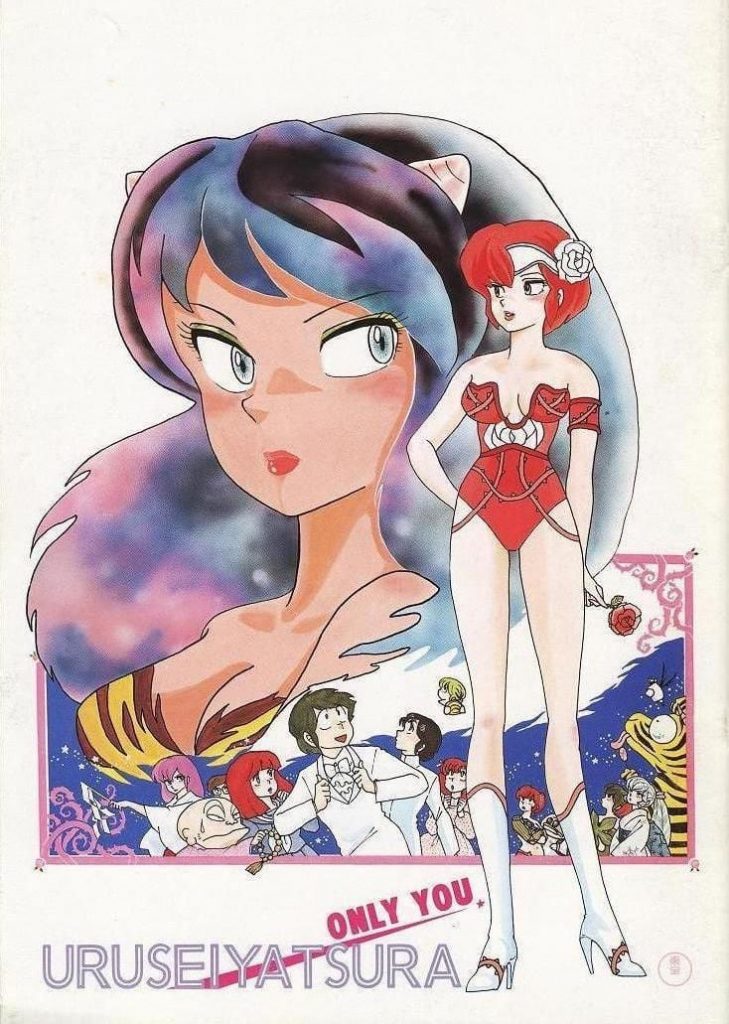

3. URUSEI YATSURA 1: ONLY YOU (1983)

Urusei Yatsura’s first cinematic adventure is also the film debut of director Mamoru Oshii, of Patlabor and Ghost in the Shell fame, and it’s one of the most beautifully artistically realized films in the series.

Urusei Yatsura’s first cinematic adventure is also the film debut of director Mamoru Oshii, of Patlabor and Ghost in the Shell fame, and it’s one of the most beautifully artistically realized films in the series.

The weight of Oshii’s subsequent body of work inevitably invites comparisons, and it’s easy to see elements of his signature visual style in their early form here. The image of flower petals falling from the sky recalls the surreal appearance of snow over the tanks in Patlabor 2; the shot looking up at an airliner flying low over urban streets resembles a similar shot in Ghost in the Shell — the immaculately framed static camera angles are something he has never left behind. There’s more to Only You than just as an early look at a celebrated director, though: it’s a gorgeous film purely in its own right. Whether it’s the medieval-cyber-organic spires of Planet Elle or the apocalyptic orange skies of suburban Tokyo, Only You has a psychedelic, alien, Roger Dean quality to its visual atmosphere, while the water features and Romanesque columns of Elle’s garden recall the elegantly ruined beauty of Hayao Miyazaki’s Castle of Cagliostro. It is a film in which no shot is wasted.

Only You also establishes the rough format that all subsequent films in the Urusei Yatsura series would follow, with the status quo of Lum and Ataru’s dysfunctional relationship threatened by an outside entity. In this case, Ataru is the one in peril, whisked away from Earth to fulfill a matrimonial destiny he set in motion as a child after winning another game of tag with an alien beauty.

The importance of the game of tag in Urusei Yatsura shouldn’t be overlooked. The series began with Ataru being forced to play tag against Lum to prevent her father from invading Earth, and the return of the game in Only You is no coincidence. Urusei Yatsura is in large part about the confusion of love when you are not grown up or experienced to navigate the its currents maturely, yet old enough to feel love’s pain and torment with devastating intensity. The teenage characters of Urusei Yatsura play love like a child’s game, but love’s consequences can be as destructive as any war. Literally. Tanks appear to roam the streets of Tomobiki Town at each fresh disturbance of the heart, while in one scene, played utterly straight for the maximum bitterly bleak humor, Lum’s father is happy to send hundreds of men out to die in a space battle, all for the sake of love.

Only You is probably the simplest of the six movies in terms of its plot, with a straightforward stop-the-wedding romantic adventure scenario that’s established right away and mostly stuck to despite the cast’s zany antics. The climax, with a drugged-looking Ataru being marched down the aisle (with Lum’s baby cousin Ten holding his ball and chain like a bride’s train) draws another parallel with Castle of Cagliostro, as well as a more obvious reference to The Graduate in the manner of rescuer Lum’s arrival.

And in casting Lum in the role of rescuer, Only You helps its own narrative dynamic. Ataru is an inherently unreliable, cowardly and selfish character who exists to get himself and others into trouble. Ataru’s new fiancée Elle is a woman who seeks to preserve love from the fickle whims of men’s hearts (she has a massive refrigerator full of hunks). Lum, meanwhile, is the opposite of fickle: completely devoted to her chosen man, she is the perfect opponent for the jaded Elle, as well as the only person who can clean up the mess the capricious Ataru has created for everyone (and make no mistake, in this film everything is Ataru’s fault).

2. URUSEI YATSURA 2: BEAUTIFUL DREAMER (1984)

Beautiful Dreamer is probably the most famous and well regarded of all the Urusei Yatsura films, and with a lot of justification. Packed with ideas, it’s also masterfully executed by returning director Mamoru Oshii, building on what he had done so well with the previous year’s Only You. Oshii is even Oshiier than before, his love of reflective surfaces in overdrive, his observations on the disquieting mundanity of Tokyo acute in his depictions of the labyrinthine suburbs and the eeriness of its silent nighttime streets. it takes the same visual flair and confident handling of the series’ vast array of characters, and channels it into a story far more ambitious.

Beautiful Dreamer is probably the most famous and well regarded of all the Urusei Yatsura films, and with a lot of justification. Packed with ideas, it’s also masterfully executed by returning director Mamoru Oshii, building on what he had done so well with the previous year’s Only You. Oshii is even Oshiier than before, his love of reflective surfaces in overdrive, his observations on the disquieting mundanity of Tokyo acute in his depictions of the labyrinthine suburbs and the eeriness of its silent nighttime streets. it takes the same visual flair and confident handling of the series’ vast array of characters, and channels it into a story far more ambitious.

Taking in time loops and multilayered realities, the movie places the characters in a timeless dream that’s at least in some way their own creation (or at least the creation of one of them, and most of the others aren’t really complaining), which makes fo

r a surprisingly peaceful apocalypse by Urusei Yatsura standards. But how to resolve this problem is itself a problem for the film. A story about a time loop or dream reality is really a problem of not being able to progress and move forward with your life: it’s a problem of being trapped by some desire or trauma or compulsion that you can’t get past. What’s especially interesting about Urusei Yatsura, though, is that the nature of weekly television means the characters are already essentially in a time loop – even if they escape from the problem Beautiful Dreamer sets up, the world they will return to still won’t let them grow or move on.

So Beautiful Dreamer is a film with bold ideas, shackled to an ending that must inevitably push the reset button and restore the weekly status quo. How does the film do that and remain satisfying? It recognizes that the dream reality itself isn’t inherently the problem: the problem is characters getting what they want. Idyllic as the life they find themselves in is, the incompatibility between the characters’ own individual dreams begin to open cracks in their shared dream reality, and its integrity starts to break down. It is the realization that they don’t want the satisfaction of their dreams. In this way, Beautiful Dreamer feels likes a meta-commentary on the nature of the show itself, with the characters endlessly denied the satisfaction of their desires, and yet somehow content in their frustration.

Beautiful Dreamer wouldn’t be such a cherished film were it just for the ambitious storyline, however. It succeeds because it handles the characters better than perhaps any other film in the series. Like Only You, it takes care to establish its core cast early on, doing so via a funny ensemble scene of escalating chaos during preparations for a school festival (the ever politically correct students of Tomobiki High have brought a tank into the classroom for their Nazi-themed café). More than that though, it manages the difficult task of making Lum and Ataru’s relationship make sense in a way that’s both broadly sympathetic to both of them and that informs and sparks off of the themes of the story. For Ataru, it’s a point of pride to never admit his affection for Lum because her presence dominates so much of his life and the world he inhabits that he feels withholding his love is the only way he can keep a shred of independence. However, as Lum admits to nurse Sakura early on, the life she has now (which for her centers completely on Ataru and their friends) is one she never really wants to change – a life built on the foundation of his capriciousness and stupidity.

Like Camus’ Sisyphus, in her eternal pursuit of the faithless Ataru, we must imagine Lum happy.

1. URUSEI YATSURA 4: LUM THE FOREVER (1986)

The most common criticism of Lum the Forever is that it’s a failed experiment: a similarly surreal but less coherently realized work than Beautiful Dreamer with a muddled plot. These are understandable criticisms, but they’re timid and cowardly criticisms too. Lum the Forever is the best Urusei Yatsura film, and a coherent story arc, philosophical framework or any two comprehensible plot elements to rub together be damned. Lum the Forever is not about plot. It laughs in the face of plot. It slaps plot’s face with its glove, tramples it to the floor and spits on its dusty, cowering body. Lum the Forever is a beautiful mess and would be diminished by anything as vulgar as a plot.

The most common criticism of Lum the Forever is that it’s a failed experiment: a similarly surreal but less coherently realized work than Beautiful Dreamer with a muddled plot. These are understandable criticisms, but they’re timid and cowardly criticisms too. Lum the Forever is the best Urusei Yatsura film, and a coherent story arc, philosophical framework or any two comprehensible plot elements to rub together be damned. Lum the Forever is not about plot. It laughs in the face of plot. It slaps plot’s face with its glove, tramples it to the floor and spits on its dusty, cowering body. Lum the Forever is a beautiful mess and would be diminished by anything as vulgar as a plot.

What it has instead is a dizzying, terrifying, beautiful, mind-expanding blizzard of images – a psychedelic collage of ideas and thematic elements that are best appreciated in a state one half-step removed from complete consciousness.

It opens with rain, a city at night, red-eyed rats, an electrical malfunction. Eyes everywhere, cameras, televisions, telescopes in space, all devoted to spying on Lum on her morning jog. Director Kazuo Yamazaki is interested in the cosmic, spiritual Lum, the oedipal alien mother goddess of Tomobiki Town, and so is someone else – in fact, apparently everybody else. There is no lovelorn kidnapper to step between Lum and Ataru this time; Lum simply fades from existence following the cutting down of an ancient cherry tree, perhaps drowned in the memories that gush forth from the tree’s wound, absorbed over years by its roots as they burrowed away beneath the town. Or perhaps not. It doesn’t matter.

Lum’s image is reflected everywhere: on every screen, in the lenses of cameras, in the compound eyes of a plague of insects. She is the focal point of a constant and massive flow of information, as countless eyes feed off her. “I didn’t know there were so many sounds,” she remarks after experiencing what looks like a sort of panic attack. She sits down to write a diary, to insist on her unique selfhood and will it into reality on paper, but she is already fading, losing herself with each click of the shutter. Perhaps it’s a comment on 1980s Japanese idol culture, with devouring obsession giving way to the easily forgotten. Or perhaps not. It doesn’t matter.

Yamazaki’s take on Urusei Yatsura always had a little more swagger than Oshii’s, a little less care and precision, a little more theatrical pomp (some might argue pretension, but what is pretension but a boring word for ambition?) Each scene in Lum the Forever plays out like a little theatrical piece in its own right, unified not by any coherent narrative but rather by an overarching atmosphere of sadness tinged by dread. Like Beautiful Dreamer, there are layered realities at work in Lum the Forever. But where Oshii always seemed to have a point even if he didn’t want to make it clear to the audience, here there is a disregard for logical progression from one layer to another that feels intentional. Some of the Tomobiki crew are making a movie, the story of which hops from genre to genre in a similarly cavalier fashion, and anyone who’s seen films from the French new wave or by Shuji Terayama knows that when there’s a film-within-a-film, it’s always a commentary on the one you’re watching.

Films are also memories, and memory is a theme that Lum the Forever returns to again and again. The students of Tomobiki High exist in a time loop, forever 17 years old but forever seeing the fading of their carefree youth just around the corner. Without Lum the cosmic mother, will it finally catch up with them? The memories that they capture this spring will be frozen for as long as film can hold them. The dreams they capture in their fantastical movie production will be preserved as well. But what happens when dreams overwhelm reality? What happens when Lum and Ataru are ripped apart and the fabric of reality is once again torn open by the trauma?

In Urusei Yatsura, usually someone starts a war, so that’s what they do this time too. But with no one to start a war against, they just start it against themselves. War is Hell, and Yamazaki depicts its thrilling action, bled of excitement for its own lack of any clear goal, and its harrowing, PTSD-ravaged aftermath. What does Ataru do? He goes for a jog.

It’s like the whole film is saying, “Look, none of this matters, nothing has any cause and effect, but everything always ends up the same in the end. Just roll with it.” There are plot elements of course – the cherry tree houses an ancient spirit; there’s a curse of some kind; the tree spirit might consider Lum to be some sort of alien infection – but Lum the Forever just isn’t interested in even pretending to link these threads together in the way the other entries in the series are. In that way, it feels like it has far more in common with the acid-fried experimental cinema of the 1970s than with its own source material.

And despite what the poster would have you believe, this may be the only Urusei Yatsura film in which Lum never wears her tigerskin bikini. Right?

And yet, Lum the Forever is also deeply affectionate towards its characters and setting. It plays like a melancholy love letter to Tomobiki Town, taking long detours into the hearts and desires of its residents. This should have been the final Urusei Yatsura movie. Its final, wryly ambiguous shot of Ataru, frame frozen in the middle of leaping towards a joyful Lum’s arms, is probably the closest thing to a true resolution that the series ever had or could have had.

Ian Martin is the author of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground.