For many American otaku, it’s The Dream: Move to Japan, learn the language, and work in animation. 20 years ago, New Orleans native David Roy did just that. We sat down in his apartment in Shibuya to discuss his life and times in the anime biz.

From an early age, Roy was interested in filmmaking, but never really considered working in animation, put off by the for-kids nature of American cartoons. But through the years, a different style caught his eye, exemplified by shows like Starblazers and Robotech, which impressed Roy with their emphasis on long-form storytelling. The final nail in the coffin came in college, when he saw Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira.

“I saw that,” said Roy, ”and I thought, ‘Man, this is something totally different. This is fantastic.’”

Roy made it his mission to get to Tokyo and study at an animation school. He arrived in Japan via the JET program, teaching English and learning Japanese for three years in Fukui Perfecture, north of Kyoto, after which he applied and was accepted to Tokyo Animation School.

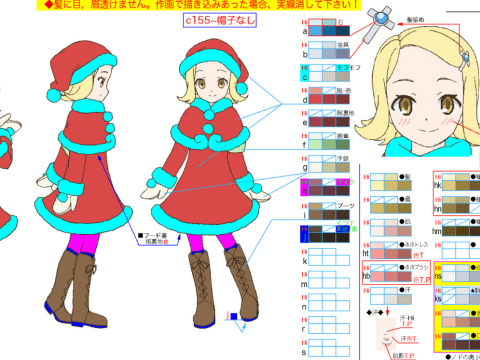

Finally in Tokyo, Roy’s anime education began. Early lessons centered on the process of drawing douga, the cels that make up the motion between two genga, or key frames. Now largely farmed out abroad, in-betweening is an unglamorous but necessary part of animation.

“A big part of it is tracing,” Roy explained as we looked over some of his school work. “This one’s pretty badly done. Look at those lines,” he laughed, pointing at an early sketch with wobbly hair. “They teach you to draw from the elbow, not the wrist. It’s gotta be one clean stroke.”

Little by little, new techniques were introduced: how to animate actions like walking, running and making movement look natural. By the end of the first year, the students were prepared to create their own short films. This was before animation was done digitally, so everything had to be done by hand. Bewildered by the difficulty of painting cels, the students asked their teacher for advice.

“He just said one word,” Roy laughed, “‘nare’ – get used to it.”

During his last year of school, Roy began job hunting, sending sketches and resumes around town. But “no one even wanted to consider a foreigner,” Roy explained, “or maybe I just wasn’t very good.” In any event, the main instructor at the school invited Roy to work in his studio doing douga. His first work was on Violinist of Hameln, followed by series like GaoGaiGar, Future GPX Cyber Formula, and Outlaw Star.

After a few years of in-betweening, Roy moved on to key animation at another studio, doing genga for Suzie-chan and Marvie, a kids’ show about cooking. After his studio lost the Suzie-chan contract, he did various gigs, including some key animation on Crayon Shin-chan and a Lupin III TV movie. But through the years, Roy’s frustration with the industry grew.

A major problem that plagued the field was money—or lack thereof. Salaries then, as now, were incredibly low. Roy was able to supplement his anime income by teaching English, but his peers weren’t so lucky. One manager wore the same torn pair of pants every day. His boss literally lived at the studio, curling up in a sleeping bag under his desk at night.

In addition, conditions were rough. Overworked and undernourished, several of Roy’s peers simply collapsed. One higher-up who pushed himself too hard ended up in the hospital for three months, after which his doctor banned him from ever working in animation again. Studios were poorly ventilated, and everyone smoked. In summer years of accumulated tobacco resin would begin to melt, dripping off the desks.

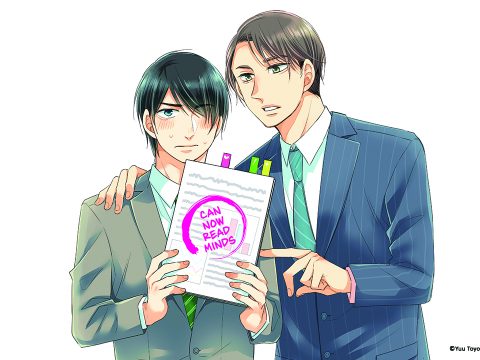

A page from one of Roy’s early sketchbooks.

“I just got sick of it,” said Roy. “I thought, ‘I cannot be in this hell.’”

Because it’s such low-paying, demanding work, Roy said, the industry only attracts the most hardcore fans, who in turn produce anime for other fans that lacks mainstream appeal. It’s part of why he doesn’t have much interest in recent productions.

“It’s not real big vision anymore,” Roy said, “it just feels like guys trying to recreate what they saw as kids.”

As one of the few foreigners working in anime, Roy got a double dose of this inward-looking mentality. His original ambition was to eventually get work promoting international co-productions. But he encountered an industry largely uninterested in partnering internationally—a reflection of Japan’s so-called Galapagos Syndrome.

Still, Roy holds out hope. He points to the work of Studio Madhouse, whose recent output has reflected that “big vision” that attracted him in the first place. A few years ago, he did some designs for the big-budget OVA Freedom, on which he had a good experience. And he’s met a few foreigners in recent years who seem to work under better conditions than he did. For Roy, the industry has a choice to make: Keep looking inward or embrace a wider market.

“Japan is well known for its animation. It should take more pride in this little treasure that it has and really develop it. Put some money into it and you’re going to get a lot of creative people coming here, and you’re going to build up a fantastic industry.”