Sword Takeda, Tim, Yuki Hijiri, Mie Hasegawa

On December 2 I teamed up for the second time with Sword Takeda and made for the little-known district of Jimbocho. Little known to American anime/manga fans, that is. I learned about it while researching my first trip back in 2007. All I needed to see was the term “used bookstores” to make it a must-see. It’s not a cornucopia like the better-known Akihabara, but if you love digging through musty old boxes for movie memorabilia, old magazines, or anime books you’ve never heard of, Jimbocho is waiting for you.

Waiting for us there on this particular day was a gentleman by the name of Hideaki Ito. Like this neighborhood, his name isn’t well-known to American anime fandom, but it should be. He and his fellow Yamato maniacs were the ones who turned their passion for the show into action that formed the first fan club, revolutionized doujinshi (fanzines) and lead the grass-roots effort to save it from obscurity. Along the way, they created what we now know as anime fandom—and they didn’t even have the word anime yet.

Hideaki Ito and his wooden cosplay Cosmogun

Ito now works for independent publisher Gin-Ei Co. Ltd., located on a Jimbocho side street in a modest 6-story walkup with a steakhouse on its ground floor. As soon as you walk in, you know you’re in serious otaku territory with books, manga, and collectibles stacked in narrow spaces. A tiny table barely big enough for two people substitutes for a meeting room. But what his office lacks in comfort is more than compensated by the breadth of his imagination and achievements. He followed his muse into the professional world when Yamato was only halfway through the production years, migrating from doujinshi to magazine publishing in 1978 when he took the reigns of OUT Magazine and went on to develop many more.

He had a hand in several mainstream Yamato books as well, and spent a lot of years documenting his other favorites, such as Tatsunoko animation and the mega-popular SF programs from ITC such as Gerry Anderson’s Thunderbirds. This work continues today with consultation for special Yamato projects from Bandai and Ito’s crowning achievement, Space Battleship Yamato Great Chronicle.

Working directly with Leiji Matsumoto, he painstakingly collected as many artifacts as he could find from the original TV series and assembled them into the single most impressive volume anyone could produce. Great Chronicle had gone on sale the day before our meeting, and a special edition would be published by Mandarake just two days later.

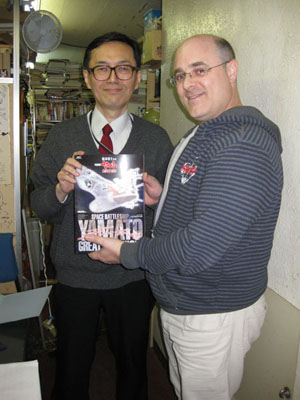

Ito and Tim with the new book

With Sword translating, we talked for a solid two hours about all things Yamato. From first to last, Ito was direct, animated, and articulate. I worried at several points in the conversation that I was keeping him from some major project, but in fact he’d just finished one (Great Chronicle) and was enjoying a lighter-than-usual workday.

Our discussion went from Ito’s pre-Yamato days living in the boondocks to his move to Tokyo for art college and his subsequent submersion into fandom. It came all the way up to the present day, a complex minefield of ownership turf and contentious relationships that go hand-in-hand with a decades-old franchise. It was a fascinating session from start to finish and says much about where Yamato has been and how far it has come. Keep an eye on future updates at starblazers.com to read the interview once it is fully translated.

My next interview came up on the morning of December 3.

Sword and I teamed up on this day to meet longtime manga artist Yuki Hijiri. If you’ve read the article about the “lost” Yamato manga at starblazers.com, you already know about him. He was the third artist to write and draw a manga adaptation while the show was originally on TV, but unlike Leiji Matsumoto and Akira Hio, his version faded into history. He became far better known for his own character, Locke the Superman, but I suspected he’d have an interesting perspective on the early phase of the Yamato phenomenon, so I enthusiastically agreed with Sword’s offer to track him down.

I didn’t know what to expect, envisioning a grumpy eldster being dragged away from his drawing board to meet us in a café in one of the monolithic Isetan department stores in Shinjuku. But when he and Mie Hasegawa (his extremely polite wife) arrived 15 minutes late owing to a car accident on the freeway (not their own, fortunately), they fell all over themselves to apologize, which was completely charming.

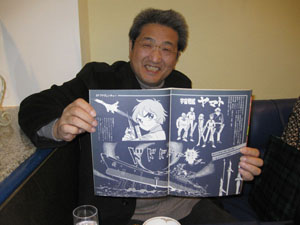

Yuki Hijiri and art from his long-lost Yamato manga

They were interested in meeting their first American comic artist, so this endeared them to me even further. We ended up talking for a solid 90 minutes, learning all sorts of things about each others’ business, finding that our shared career experience allowed us to speak the same language even though we didn’t. As with the Ito interview, this one will also be published at starblazers.com at a later date.

Meanwhile, if you read part 1 of this travelogue, you might be wondering what became of our thwarted attempt to meet Leiji Matsumoto. Yes, there is more to the story.

After our interview with Hideaki Ito, Sword and I wandered around Jimbocho in a daze, having absorbed as concentrated a dose of history as we could have wanted, and I realized it was time for Sword to place a call to the Leiji Matsumoto household. He’d made an appointment the previous night to call in and ask for another appointment. (It’s complicated.)

I milled around on the sidewalk while he talked, and when I heard him shout “Thank you very much!” loud enough to echo across the street I knew we were back in business. Interestingly, it was our nature as visitors from distant lands that kept the master’s interest. And apparently that interest ran pretty deep; we had just been invited to his house.

Visit starblazers.com right now for news about the Yamato movie and much more.