To today’s anime fan, the OVA, or Original Video Animation, a piece of work made for the home video market, is an essential and everyday staple of the medium. You’ll see OVAs developed to hawk popular manga, utilized as sequels for existing works, and used as platforms for intriguing original stories. 25 years ago, however, OVAs as we know them really didn’t exist. It took some brave souls to take that big first step into the then-new home video market; those brave souls were Studio Pierrot, and in 1983 they took the plunge with Dallos, a 4-part OVA series directed by the relatively unheralded (at the time) Mamoru Oshii.

Even 25 years later, Dallos is an intriguing piece of work. It’s a tale of revolution that, at times, seems pretty heavily cribbed from Robert Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, the famed novella about a lunar revolution in the far future. Dallos takes this simple premise—the idea of an oppressed underclass of miners on the moon using their powerful mining equipment as the tools of rebellion—and adds a singular rivalry, between idealistic Shun Nonomura and authoritarian Alex Rigel. Rigel is a newcomer to the moon, and stands ready to put down the occasional uprisings of the locals quite violently, failing to understand that his harsh measures will only lead to more discontent. Nonomura, on the other hand, is a nice kid who quite accidentally falls into line with the rebels. At the center of the conflict between the lunarians and the oppressive Terran government is Dallos, a mysterious alien artifact (it looks kinda like Cydonia, the famous “face” on the surface of Mars) that the locals worship as a god.

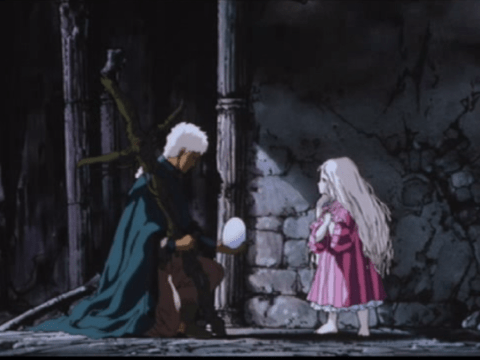

One of the original rationales for creating OVAs was the ability to use a higher budget than that seen in TV animation. Director Oshii certainly takes advantage of this, presenting dynamic, fluid combat sequences to break up his trademark lengthy scenes of intellectual conflict and political intrigue. In Dallos’s story, you see, Rigel isn’t absolutely evil—he desperately wants to prove himself as a strong leader and sees a nasty, short-term fight as necessary to return life to normal for both Lunarians and Terrans. On the same note, Nonomura isn’t absolutely good; once the fighting spills over to his own friends and family, he readily takes up arms against the attackers, and is ambivalent about what to do with his rebel cell’s first P.O.W., a rich, well-connected girl who just happens to be Rigel’s fiancée.

Dallos does have its share of finer points—its action sequences involve cascades of spent shells, brilliantly detailed explosions, and a few neat scenes where the chief weapons are cybernetically-enhanced dogs—dogs with red spectacles. Hey, wait a minute! Character designs, by Toshiyasu Okada (Area 88, Mysterious Cities of Gold) are intriguing, bridging the gap between the simple designs of the 70s and the more detailed, streamlined designs of the 80s. Some of Oshii’s depictions of the reality of the conflict are striking, in particular a sequence when a group of dead civilians are unearthed—all that remains of them are their metal headbands. One of Dallos’ best points is the way Oshii humanizes both sides of the conflict—just as in his later Jin-Roh, there are heroes and scoundrels on both sides of the fight.

Dallos is intriguing and, at times, spectacular to watch. It was remastered for DVD release in Japan a few years ago, and looks quite good for its age. But it was ultimately a production fraught with problems—schedule and budget issues would see the third and final episode split into two unwieldy parts, and to call the final episode’s ending unsatisfactory would be something of an understatement. OVAs have a grand tradition of either succeeding wildly or falling apart, ending without a proper finish, and Dallos does a bit of both. 25 years later, Dallos stands as a harbinger of the great first wave of OVAs, classics like Megazone 23 and To-Y, and a fascinating look at an early work by one of anime’s masters.